Orson Welles called cinema “a ribbon of dream,” and many others have described film in similar ways (Rees). Freud wrote, “To interpret a dream is to specify its meaning, to replace it by something which takes its position in the concatenation of our psychic activities as a link of definite importance and value.” (Freud). By examining the relationships of characters in a narrative, and by considering how a theme such as violence affects the characters’ lives, it is possible to interpret new meanings from stories in the same way that Freud believed new meaning could be taken from dream analysis.

Narratives, particularly in Hollywood films, have a tendency to place murder in the close-quarters setting of a family. The experience of watching a film can be very intimate, and the goal of many filmmakers is to use that intimacy for their own purposes; wether for entertainment, shock, or philosophical discussion, the filmmaker achieves his goal of communicating with the audience by manipulating their relationship to characters on the screen. If the subject of a film is murder filmmakers will often place the crime, or the criminal, within an established and relatable setting such as a loving family or community. In this way the audience does not guard itself against the on-screen characters the same way they would if the film were set in an unpleasant location and populated by unappealing characters. When the barrier between audience and character is down it is possible for filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock or David Lynch, and for novelists like Salley Vickers, to affect their audiences with deeper, more memorable characters.

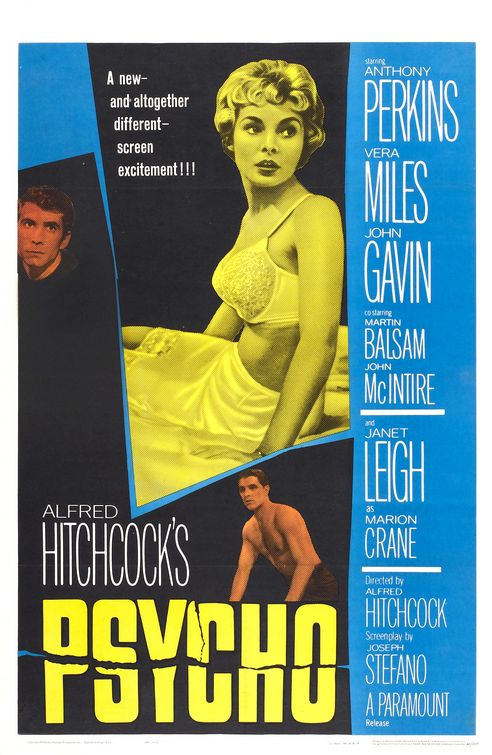

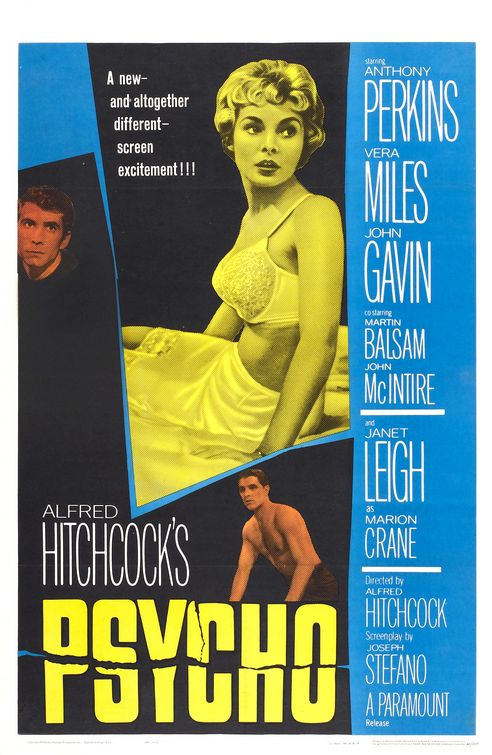

The crime classic Fargo, made by Joel and Ethan Coen, establishes a story of murder and kidnapping in an unappealing environment (North Dakota in winter) that is filled with timid, violent, irrational, and foolish characters. Approximately 30 minutes into the film, Marge Gunderson is introduced. She and her husband Norm are the happy couple at the center of this unpleasant cast of characters. As a result she is the character that the audience relates to and cares about the most. When the climax of the film puts her in danger it creates a stronger suspense reaction because it is not only a dangerous situation, it is a dangerous situation for the character to whom the audience has become emotionally attached. This juxtaposition of relatable characters or environments with violence and murder is key to films such as Cape Fear, Domestic Disturbance, Red State, Psycho, and Blue Velvet.

Stories that place emphasis on the collision of family and violence must deal with related themes and resulting actions. In Woody Allen’s 2007 thriller Cassandra’s Dream, violence is introduced to a very normal family when two brothers are given the option to escape their financial problems by committing murder for a rich relative. This story is, on the surface, about the morality of murder, but it is also an examination of familial loyalty because of the characters involved. When a murderer has no real or surrogate family the story does not address these subordinate themes, but the presence of family in a story about violence dictates that themes such as guilt, secrecy, loyalty, and voyeurism must be addressed for the story to appear complete.

The confession, in both a religious and a legal sense, is a trope in dramatic fiction to satisfy a plot that involves a character’s guilt as a driving force. The first act of Psycho focuses on Marion Crane’s guilt as she attempts to flee Phoenix with stolen money. Until she confesses to Norman that she has “stepped into a private trap” and wants to return to Phoenix to extricate herself, Marion’s guilt is the driving force of the plot and suspense, and it is the defining feature of her character. Similarly, in Salley Vickers’ novel Where Three Roads Meet, an aspect of the character of Sigmund Freud is revealed when he confesses “I begin to feel I can’t take much more of this infernal pain.” This admission of weakness is not something he feels he can say to his wife or daughter (109). Tiresias tells him “It is itself a kindness to accept kindness,” which reflects his high opinion of the doctor (155). Freud is shown in these passages to be a man protecting his family because of his love of them and because of his guilt for keeping them at a distance. In both Psycho and the novel the inclusion of guilt is a result of the plot’s effect on the stories’ characters. Marion has stolen money, so she feels guilty as a result. Dr. Freud has isolated himself to continue listening to Tiresias, so he feels guilty for the effect on his family.

Like the guilt that drove Marion, curiosity drives Norman and several other characters in Psycho. Norman is interested in Marion and his curiosity leads him to invite her for dinner, which puts him into conflict with ‘Mother’ and leads to the first murder. Norman’s curiosity becomes voyeurism when he uses a hidden hole to spy on Marion as she undresses for her shower, and the surface emotion, curiosity, leads to the deeper, ‘Mother’ part of his psyche to commit the violent act of jealous murder. Curiosity also drives Marion’s sister to seek out Sam, leads both characters to investigate Marion’s disappearance, and sends Detective Arbogast into Norman’s house. When ‘Mother’ attacks Arbogast it is a panic defense to protect Norman from what Arbogast’s curiosity could uncover. Through this series of acts and violent responses, Hitchcock draws the audience ever-closer to Norman’s violent secret. As the driving force of the main characters, curiosity is the driving force of the film as a whole. Even Marion’s guilt during the first half is set off by an act of curiosity: could she get take the money and run?

In much the same way that Psycho is driven by curiosity, Blue Velvet is driven by suspicion. Jeffrey Beaumont becomes suspicious of his picturesque town when he discovers the severed ear on his way home. His suspicions lead him to the apartment of Dorothy Vallens, and he betrays his honest, boy-next-door exterior by sneaking into her apartment. Jeffrey’s suspicion leads him to witness Frank and Dorothy’s disturbing relationship and then to be discovered and chastised by Dorothy. Suspicion drives the paranoid actions of Frank Booth as he reacts to Jeffrey’s presence, and hope (an optimistic alternative to suspicion) drives Dorothy to continue fighting to get her husband and child released.

Neither Norman Bates or Jeffrey Beaumont appear to be violent at the start. Both are relatable and, like Marge in Fargo, are main characters whom the audience can care about. Starting with these relatable characters the two films successfully place the audience into situations of violence and danger without alienating viewers to the point of wanting to leave. This makes the unmasking of ‘Mother’ and Jeffrey’s journey down the rabbit hole all the more suspenseful because the audience is emotionally involved in the main characters and shares the curiosity and suspicion that drive their stories.

The intimate actions of curiosity and suspicion, voyeurism and surveillance, murder and sexual abuse, place the characters of Psycho and Blue Velvet in the position of being as intimate with each other as they would be with family, except in a far more extreme and traumatic form. Jeffrey’s journey into the dark world of Frank and Dorothy’s relationship coincides with the hospitalization of his own father. Until the final scene, when Jeffrey wakes up to see his father at the barbecue, Jeffrey is never the passive family member in any scene. His interactions with his mother and aunt are in passing, as he is heading to work or out into the night and they are sitting in front of the television. His interactions with Frank and Dorothy, however, place him in a passive role as he is told where to go and what to do by both characters. These two situations place Jeffrey at the extreme ends of a child’s existence. With his real family he is the adult caring for aging parents, and with Frank and Dorothy he is reduced to a toddler being ordered around and punished for bad behaviour.

In Psycho, Norman’s interactions with the visitors to his hotel are always interruptions to his relationship with ‘Mother.’ His time with Marion causes ‘Mother’ to lash out like a jealous lover, the trespassing Detective Arbogast triggers the panic defense of a parent protecting a child, and the investigations of Sam and Marion’s sister cause Norman to act out as the protective son. These responses are archetypal of family bonds, but the violent form that the responses take, combined with the fact that Norman and ‘Mother’ occupy the same body, makes them extreme, abnormal reactions to the curiosity that drives the story.

The collision of family dynamics and violence has been an endless mine of stories for books and Hollywood movies. Wether the family are homicidal maniacs (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), vigilantes (The Boondock Saints), God-appointed avengers (Frailty), motel owners, or intimate strangers, they create ripples in the world around them that have caused the events central to many films and novels. By considering these ripples of cause and effect in a narrative it is possible to interpret meaning from stories in the same way that Freud took meaning from dreams.

Blue Velvet. Dir. David Lynch. Perf. Isabella Rossellini, Kyle MacLachlan, Dennis Hopper, and Laura Dern. MGM, 1986.

The Boondock Saints. Dir. Troy Duffy. Perf. Willem Dafoe, Sean Patrick Flanery, and Norman Reedus. 20th Century Fox, 1999.

Cape Fear. Dir. J. Lee Thompson. Perf. Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum. Universal, 1962.

Cassandra’s Dream. Dir. Woody Allen. Perf. Colin Farrell, Ewan McGregor, and Tom Wilkinson. Weinstein Company, 2007.

Domestic Disturbance. Dir. Harold Becker. Perf. John Travolta, Vince Vaughn, Matthew O’Leary, and James Lashly. Paramount, 2001.

Fargo. Dir. Joel Coen and Ethan Coen. Perf. Frances McDormand, William H. Macy, Steve Buscemi, and Peter Stormare. 20th Century Fox, 1996.

Frailty. Dir. Bill Paxton. Perf. Bill Paxton, Matthew McConaughey, Powers Booth, Matt O’Leary, and Jeremy Sumpter. Lions Gate Films, 2001.

Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. psychclassics.yorku.ca. York University, 1997. Web. 5 Feb. 2012.

Psycho. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Perf. Anthony Perkins, Vera Miles, John Gavin, Martin Balsam, and Janet Leigh. Universal, 1960.

Red State. Dir. Kevin Smith. Perf. Michael Parks, Melissa Leo, John Goodman, Michael Angarano, and Stephen Root. Smodcast, 2011.

Rees, Nigel. Cassell’s Movie Quotations. London: Cassell & Co, 2002. Print.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Dir. Tobe Hooper. Perf. Marilyn Burns, Edwin Neal, and Allen Danziger. Bryanston Distributing, 1974.

Vickers, Salley. Where Three Roads Meet. Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2007. Print.