Stanley Kramer’s careful direction and the cast’s intense performances made Judgment at Nuremberg a very powerful film to watch. During the opening of the trial the director shows the exhausting process of translation that was required at the multi-lingual trials, and throughout the film were powerful interrogations and speeches, which are the scenes that I will remember best. Overall I felt that Judgment at Nuremberg was a very interesting film, which both entertained and illuminated the historical era.

The way Stanley Kramer shows the translation process at the trial lasts for a significant amount of time. Often the problem of translation is overlooked in Hollywood films, usually by assuming that everyone is able to speak English. The repetition of lines through the various translators, and a moment where Spencer Tracy asks the defense lawyer to slow down for the translation, create an image of extreme authenticity. This doesn’t last forever, but it is sustained as long as is necessary before a zoom shot makes the transition to all-English. By establishing these rules Stanley Kramer brought me a step closer to believing in the film’s reality.

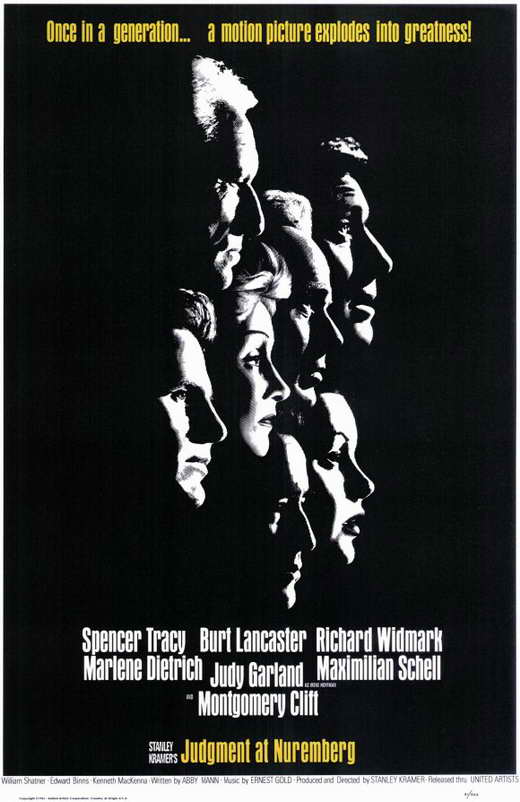

I felt the most powerful part of the film was the cast. Judy Garland’s emotional trauma, Maximilian Schell’s relentless interrogation, and Spencer Tracy’s solemn conclusion were all very engaging performances, which effectively hid the film’s long run time. A criticism that always comes to mind when I watch this style of war film – epic Hollywood productions with major stars in every role – is from the opening chapter of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. He retells a scene where he spoke to the wife of an army friend, years after the war, when he was researching his book. She scolds him and says “You’ll pretend you were men instead of babies, and you’ll be played in the movies by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne or some of those other glamorous, war-loving, dirty old men. And war will look just wonderful, so we’ll have a lot more of them.” Often, in films from the 1960s and 1970s at least, history seems free of youth except for the children who appear as victims. The film, by telling the story of a trial and not a battle, does not misrepresent its characters by having older actors play the parts, but it is guilty of glamorizing history. The beautiful Marlene Dietrich, the rugged Burt Lancaster, and the wise Spencer Tracy are all an important part of the films impact, but also a necessary part of the film’s glossy surface. A documentary about the trials, or a film with unknown performers, would likely have failed to be the successful classic that Judgment at Nuremberg is. Therefore it is a balancing act, which Stanley Kramer walked as best as possible, to engage a star-hungry audience and tell an important story.

By the end of the film I felt I had experienced a proper classic. Sometime I find that older social and political films can become obsolete in their opinions, but the philosophical debate at the heart of Judgment at Nuremberg still feels relevant today.

Works Cited

Judgment at Nuremberg. DVD. Directed by Stanley Kramer. 1961.

Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-Five. New York: Random House, 1969.